From Side Hustle to Social Pressure

posted 16th January 2026

When Side Hustles Start to Resemble Cult Dynamics

In recent years, social media — particularly Facebook — has become increasingly saturated with posts promoting vague “side hustles”. These opportunities are often framed as low-cost subscription memberships promising freedom, flexibility, and personal growth, while remaining notably unclear about what is actually being sold. Many people scroll past them without much thought, but others are beginning to feel uneasy about how widespread they have become — and how many women, in particular, appear to be signing up.

This discomfort is not rooted in cynicism or judgement. It comes from noticing patterns. From a psychological perspective, what is most interesting is not who joins these schemes, but how they work — and why they are so effective.

This article is not about criticising individuals who participate. Many people who join are navigating genuine life transitions: career dissatisfaction, caring responsibilities, financial pressure, or questions of identity and purpose. Instead, this piece explores how certain recruitment-driven models draw on well-established psychological processes that can influence anyone.

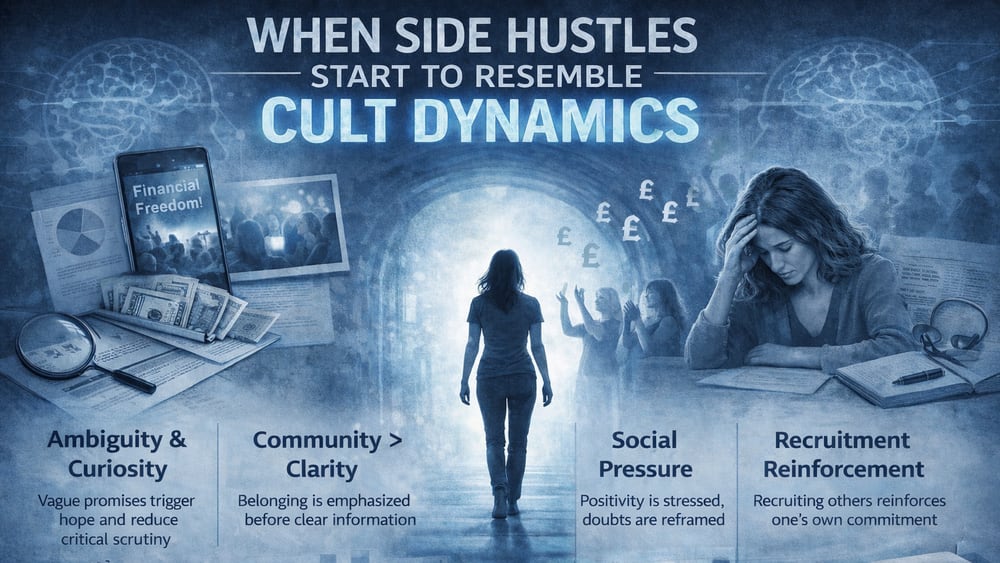

Ambiguity, Curiosity, and the Pull of Possibility

One of the most striking features of these schemes is their deliberate vagueness. Posts rarely explain the product, the business model, or how income is generated. Instead, they rely on language such as “subscription economy”, “membership club”, or “no product pushing”.

From a psychological standpoint, ambiguity is powerful. Research in social and cognitive psychology shows that when information is withheld, curiosity increases and critical scrutiny often decreases. People tend to fill gaps with their own hopes and assumptions — particularly when the financial cost of entry feels small enough to be “worth a try”. Low commitment lowers defences.

This is not irrational behaviour. It is a predictable human response to uncertainty combined with optimism.

Community Before Clarity

Once interest is expressed, individuals are usually directed into private online groups. This shift is psychologically significant. Studies of group dynamics consistently show that belonging often precedes belief. Rather than being persuaded through transparent information, people are first immersed in an environment of encouragement, success stories, emotional disclosures, and shared language.

Over time, the group itself becomes reinforcing. Participation brings validation, routine, and connection. Leaving can begin to feel less like opting out of a business opportunity and more like stepping away from a community or a developing identity.

This sequence — social immersion first, explanation later — is a pattern long observed in high-commitment groups, including those described in research on cultic influence. The parallel is not that these schemes are cults, but that they rely on similar psychological processes.

Positivity, Belief, and Social Pressure

Another common feature is the strong emphasis on positivity. Doubt or scepticism is often reframed as “negative mindset”, “fear-based thinking”, or “self-limiting beliefs”. While this language appears empowering, it can subtly discourage reflection.

From the perspective of social psychology, this reflects normative social influence — the pressure to align emotionally and cognitively with group norms in order to remain accepted. Over time, people may learn which feelings are welcomed and which are quietly invalidated. Critical thinking is not overtly banned, but it is gently made uncomfortable.

This does not require coercion. Humans are highly attuned to social feedback, and most people adjust themselves to preserve belonging.

Recruitment as Reinforcement

Although these schemes often describe themselves as selling digital products or memberships, income is typically driven by recruitment. Recruiting others serves not only a financial function, but a psychological one. Encouraging someone else to join reinforces one’s own decision, reduces internal doubt, and strengthens commitment.

This dynamic is well recognised in psychology. Belief is often consolidated through action rather than evidence. The more effort someone invests — particularly when that effort involves persuading others — the harder it becomes to step back and reassess.

Why It Can Feel Positive at First

It is important to acknowledge that participation is not universally negative. Many people experience genuine benefits, particularly early on. These can include increased confidence, a sense of purpose, reduced isolation, and renewed motivation. From a psychological perspective, this is understandable. Humans thrive when they experience belonging, validation, and structure.

For individuals who have felt unseen or undervalued — particularly during periods of transition — these experiences can feel meaningful and restorative. Dismissing this as illusion would be inaccurate and unfair. The emotional benefits are often real.

When It Becomes Harmful

Difficulties tend to arise when those benefits become conditional. When belonging is tied to constant positivity, ongoing payment, or continued recruitment, the experience can shift from supportive to pressurised. When financial outcomes fail to match expectations, individuals may experience cognitive dissonance — the discomfort that arises when reality conflicts with belief.

Rather than being encouraged to question the system, participants are often subtly guided to “believe more”, “work harder”, or recruit further. Responsibility is internalised, while structural limitations remain unexamined.

In several widely reported cases, recruitment-driven organisations have been associated with significant harm. For example, investigations into companies such as LulaRoe revealed patterns of mounting debt, pressure to recruit friends and family, and widespread financial loss among participants. Herbalife has faced regulatory action and settlements related to its recruitment practices, and OneCoin, marketed as a digital currency opportunity, ultimately collapsed and was prosecuted internationally as a large-scale fraud.

These cases differ in scale and legality, but they share recurring psychological themes: opaque structures, emphasis on belief over evidence, and the reframing of failure as personal inadequacy.

The Psychological Cost of Disengaging

From a therapeutic perspective, one of the most concerning outcomes is not financial loss alone, but the erosion of self-trust. When people are repeatedly told that lack of success reflects insufficient belief or effort, they may internalise blame rather than recognising systemic constraints. This can impact self-esteem, increase anxiety, and leave individuals vulnerable to similar influence in the future.

Leaving such groups can also be psychologically difficult. The loss of community, routine, and shared meaning can feel abrupt and destabilising, particularly if the group has become a primary source of social connection. This mirrors patterns observed in other high-commitment environments, where exit involves emotional as well as practical adjustment.

Why This Feels Like It’s “Getting Out of Hand”

The growing visibility of these schemes can feel troubling not because people are foolish, but because the scale normalises what should be high-risk decisions. Emotional persuasion replaces transparency, recruitment is framed as empowerment, and questioning is subtly discouraged.

From a psychological perspective, concern about this trend reflects awareness — not judgement. These systems work because they draw on universal human needs for belonging, agency, and hope. None of us are immune to social influence.

Recognising the parallels between recruitment-driven online schemes and cult-like dynamics is not about alarmism. It is about understanding influence. A psychologically healthy response is not ridicule or dismissal, but awareness. Curiosity does not need to disappear — but it benefits from being accompanied by clarity.

People are not wrong for seeking connection, purpose, or financial independence. The difficulty arises when those needs are met within systems that prioritise growth and recruitment over transparency, sustainability, and psychological safety.

Understanding these dynamics allows individuals to pause, reflect, and make informed choices — without shame, self-blame, or fear.